PAM takes you back to when Ghanaians were living the hiplife, a 1990s musical and generational craze which placed hip-hop verses in-between highlife guitar loops.

If there is one country in Anglophone West Africa capable of challenging the undeniable Nigerian hegemony over contemporary pop music, it is probably Ghana. A relatively small territory of around 30 million inhabitants, the country has for decades been a continental hotspot for the most exciting genres. Around 2010, Ghanaian music was taking the world by storm with azonto, and in the 1960s, the country birthed highlife, which played an immense role in nurturing Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat and contemporary Afrobeats, of which the origins are also often attributed to the country of Kwame Nkrumah. However, between highlife and Afrobeats, a vibrant and equally influential period of music thrived in Ghana: the 1990s, pulsed by the irresistible and ultra-catchy sound of hiplife.

In 1957, Ghana famously became the first African country to gain independence. Highlife was the fashionable music of that era, the original soundtrack of the local elites who gathered for parties where people dressed in suits and top hats. Powered by legends such as E.T. Mensah, and later the greats Ebo Taylor, Gyedu-Blay Ambolley and Pat Thomas among others, highlife was a profoundly nocturnal genre, with an economy that relied on live shows. The “clubs”, dance bars with a stage, were this music’s main disseminators, each of them having its own band while some people carried gramophones in markets and busy streets to make some money out of the latest highlife hits.

Yet, in 1966, the country went through a turbulent political period: Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown by a coup. In 1979, after a series of shady elections and other coups, Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings took power by force and imposed a curfew on Accra. This nightlife ban completely changed the cultural landscape of the city, and the highlife scene, which had mostly existed through the nightclubs, died out. In addition, in 1983, the Ghanaian government implemented Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs), which led to an important economic liberalization of the country. The informal economy grew considerably, leading to the opening of many self-owned bars and clubs launched in private properties and personal backyards, with cheap, loud speakers replacing the former live bands. More and more radio channels were created, with a need for short and catchy tunes. Electronic production equipment became accessible, and artists naturally turned to homemade, self-produced music, looping and tinkering with their favorite highlife tracks. Finally, in a neoliberal economic landscape with less and less funding and action from the government, living conditions dramatically decreased, with housing conditions relatively worse in 1980 than in the 1950s. The Ghanaian audience found itself in great need of a voice to express their frustrations.

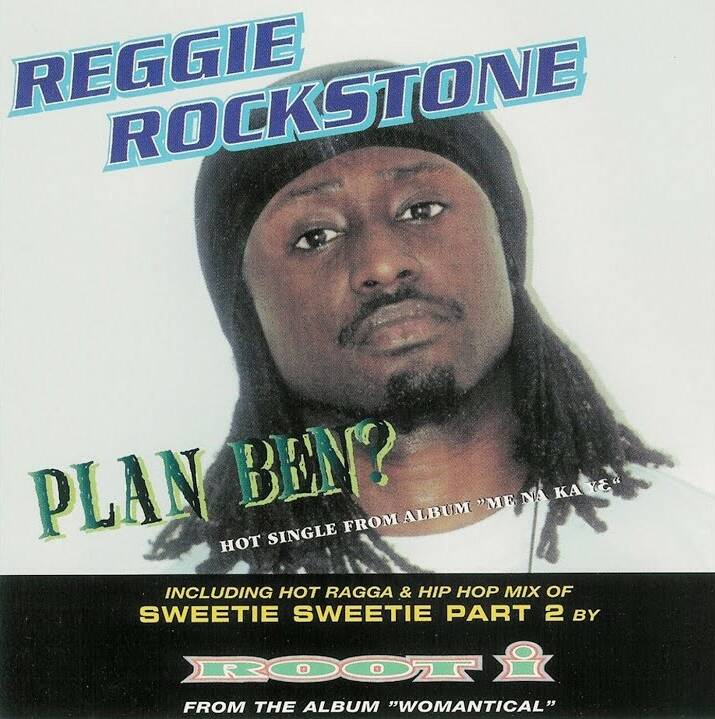

It was in this turbulent context that hiplife was born. A young generation, who hadn’t lived under British colonialism, but was experiencing a brutal economic downfall, started seeing the American hip-hop superstars as their new social models, at a time when rap was starting to become global. Unlike in the United States, the first Ghanaian rappers often came from comfortable situations that allowed them to travel to Europe and America, where they were able to be updated on the latest Occidental trends – Reggie Rockstone himself was born in the UK and spent a certain period living in the US. However, Ghanaian artists of lower social classes also ended up joining the movement, with hip-hop allowing them to produce music cheaply and to express their frustrations. Rather than exactly mimicking their colleagues across the Atlantic, the producers incorporated highlife elements, with distinctive guitar loops or drum samples, and started rapping in Twi, Akan or Ga about their local stories.

It is hard to say who truly invented or pioneered hiplife. While Reggie Rockstone is hailed as the “Godfather” of the genre since his debut album Makaa Maka, we could argue that the first mix between highlife and hip-hop was truly made by Gyedu Blay-Ambolley on his hit “Simigwado”, released in 1973. The track, around 1:18, clearly features him “rapping” his lyrics over a highlife/funk fusion. Other musicians such as KK Kabobo, who had an active career in the 1980s, could also be cited. Nevertheless, the 1990s remain the era of hiplife, with bands such as Talking Drums fully embodying hip-hop culture and imagery, with obvious influence from the US. The duo, composed of Kwaku-T and Bayku, released the visuals for “Aden” in 1993; the song’s Youtube title credits them as “Ghana’s First Hip Hop Group”.

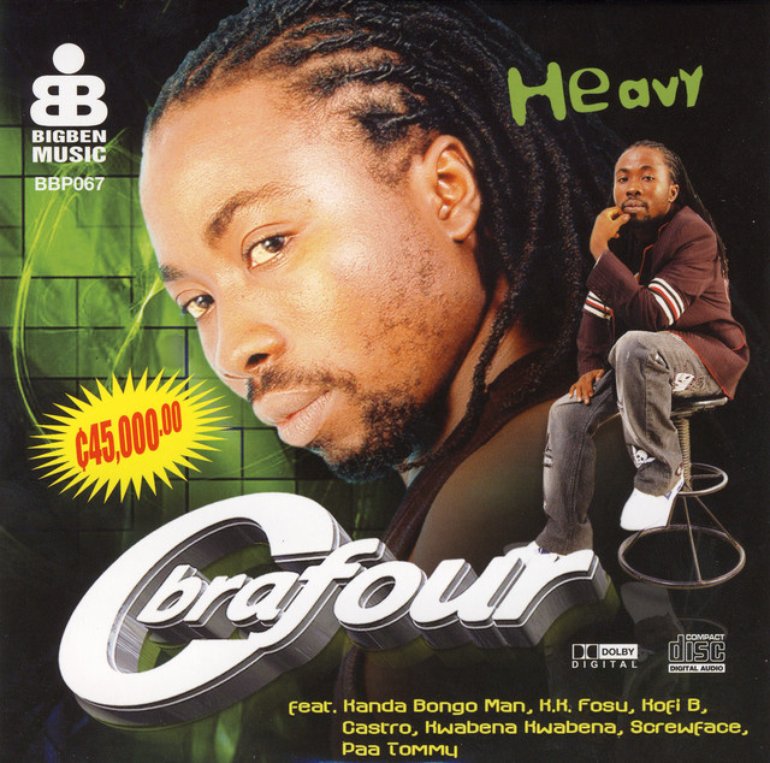

As in every new genre championed by a young generation, embittered elders were quick to criticize, stating that it was foreign and didn’t fit in the country’s landscape. To that, hiplife artists and supporters kept arguing that the genre was profoundly Ghanaian. First of all, the sound itself was hybrid. Producers like Jay Q went even deeper than highlife into the Ghanaian musical heritage, adding flavors of kpanlogo or jama in his beats, genres that emerged in rural zones of the country. Second, the language, the slang, the proverbs, the bravado, the expression and the humor used in hiplife songs were nothing if not local. As the two members of Buk Bak sang about “Trotro”, the iconic Accra taxi minibusses, Reggie Rockstone had a hit named “Nightlife in Accra” while Obrafour rapped about “Kwame Nkrumah” himself. As researcher Esi Sutherland-Addy says in the trailer of the documentary Living the Hiplife, “It’s amazing that they’ve taken on the form of hip-hop, and the content is so Ghanaian. […] There is this whole culture of seeing themselves as having the right to speak”.

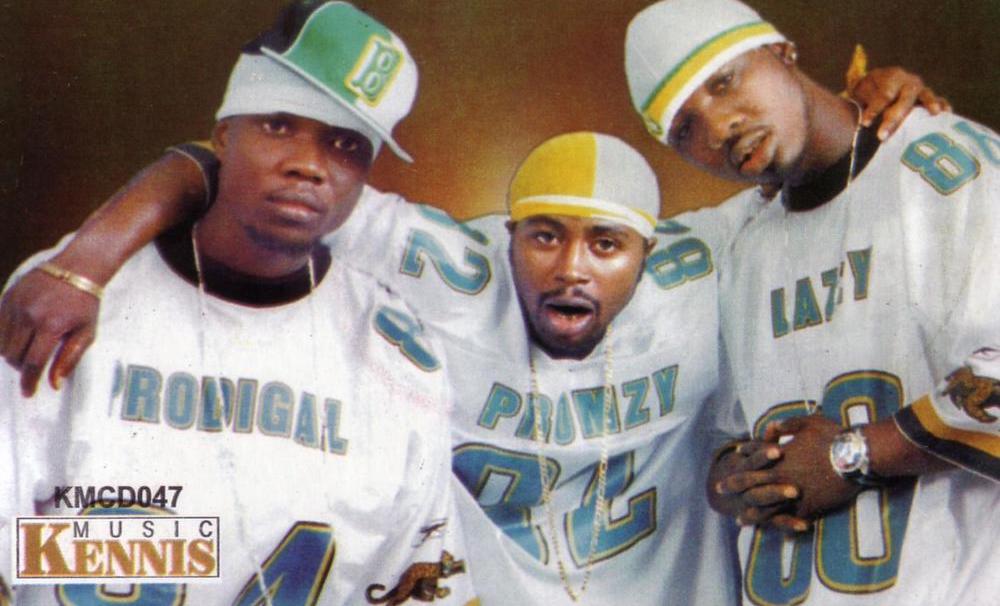

Indeed, hiplife gave many artists and individuals from economically marginalized communities the “right to speak”. Yet, did it really take on the politically engaged and revolutionary dimension of American rap? The answer is complicated. Some hiplife tracks did have some political content in their lyrics. Reggie Rockstone’s “Makaa Maka Pt. 2”, for example, sees him saddened by the lack of “lawyers and doctors” in his country, and warns the listener against the dangers of drugs. However, most of the mainstream hiplife was actually designed for you to enjoy yourself and have fun.These were hip-hop party songs filled with bravado and humor, or dancefloor cuts with catchy beats and choruses, just like highlife twenty years before. Yet, these songs have to be put back into a context of an important economic crisis and wide poverty. By rapping about trivial subjects, dressing according to the latest Brooklyn trends and absorbing Black American codes, a lot of Ghanaian artists were also loudly expressing their dreams of other horizons while promoting a new, urban and modern Ghanaian identity. Even though VIP’s lyrics, written in the tough neighborhood of Nima, often speaks about girls, having fun and partying; can’t we also hear their desperate will to leave an economically oppressive model? Wouldn’t that be political? Like all great hip-hop it’s up for interpretation.

With time, it has to be recognized that hiplife as such has lost its branding. With the rise of global hip-hop, the heirs of the genre ended up being simply called “rappers”. The phenomenal rise of Ghanaian drill, however, can be seen as a direct consequence of the hiplife era: hip-hop would probably not be so popular in the country if 1990s artists hadn’t pushed it so strongly. The genre also still lives in the directions taken by mainstream Ghanaian music. Azonto, for example, can be seen as hiplife 2.0, with artists once again rapping on West-African infused beats (see Guru’s “Akayida”). The Ghanaian dancehall scene is also closely intertwined with hiplife: Shatta Wale, before being the “African Dancehall King”, had his first hit in 2003 with Tinny on “Moko Hoo”, a track with a clear hiplife feel to it.

More than existing through inspiration and new subgenres, hiplife also still lives through concrete new releases. Artists like R2Bees, still active and popular, keep on releasing pure hiplife tracks, blended with Afrobeats and dancehall influences; Kuami Eugene, Ghana’s rockstar, recently invited TiC (ex Tic Tac) on “Pt2” of the rapper’s 2003 love anthem “Kwani Kwani”. Maybe the best example of the genre’s legacy is VIP’s classic “Ahomka Womu”. The track crossed Ghanaian borders shortly after its release with a cover from Nigerian singer Mama G (“Make We Jolly”), then reappeared in Nigeria in 2017 with Wizkid’s “Manya”, and ended up switching continents with London-based Kida Kudz’s “1am”, which clearly samples it. From Accra to London through Nigeria, the track has followed the path of highlife in the 1970s, and contemporary Afrobeats. A proof of the formidable capacity of Ghanaian music to export itself, while always staying true to its roots.